Desperate times are the season for unicorns.

Healthcare is no exception.

“Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) may actually be the unicorns we’ve been waiting for, spreading their cost-saving magic throughout the health system.”

If in addition the unicorns dance under a rainbow, times must be particularly bad.

Michael McWilliams is indeed an inspiring speaker and has done some of the most authoritative research in the area. It was therefore great to have him in London during April 2017 as part of an NHS event expertly chaired by Michael Macdonnell and hosted by the Health Foundation. But by his own admission, if there is something mythical about ACOs, it is that they have delivered at all, against the odds of a difficult, and in parts ill-designed, policy context.

I was fortunate enough to have been asked to provide a response to Michael McWilliams talk. We have taken a keen interest in ACOs over the years, not least because several of our member organisations in North West London are experimenting with integrated and coordinated care including one of the national Cancer Vanguards. Looking to Europe and the US to understand what works and distil that learning to support our partners is part of what we do.

What follows are observations from a recent visit to Baltimore and Maryland as well as the CMS with my colleague Shirlene Oh. These are not all based on hard evidence at this stage, but are the views of an interested by-stander.

“In God we trust. All others must bring data” (W. Edwards Deming)

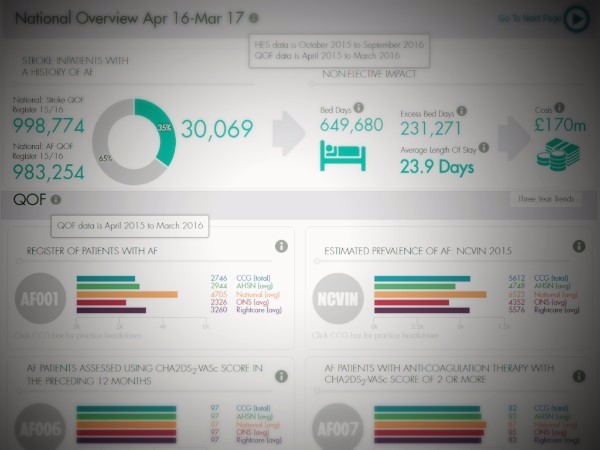

And so they do. There was not one conversation or visit without a major focus on data, and more importantly the use of data to drive care and operational decisions.

It did not necessarily seem the case that the US data is richer or better than what we have in the NHS. But the investment in data intelligence and analytical firepower stands in no comparison to ours. This is also very true for the European systems we have looked at and are working with such as OptiMedis and Ribera Salud.

Analytical teams in these organisations are large and not solely focused on coding for billing (that too of course) but on business intelligence. I’ve always felt an ache when seeing how much patient level data goes un-utilised in the NHS especially given the effort it still takes to move from paper to EPR systems.

Demand drives supply and it may just be the case that demand amongst most executive teams in the NHS is primarily for data on national targets rather than organisational insights to drive change and innovation. There are exceptions; the National Cancer Data Repository and some of the national Mental Health data are great resources, but again often underused.

The focus on data is also replicated at the national level. The CMS is (at least for now) publishing ACO data and there are clear financial and quality indicators. This is also true in Spain and Germany. This stands in sharp contrast to how we look at the Vanguard project. Three years in, there is very little high quality comparable and transparent data in the public domain.

“As you sow so shall you reap” (Galatians VI)

Analytical teams don’t come cheap and neither does the transformation from fee for service to population health. ACO development costs money and requires dedicated resource. Some surveys found that setting up an ACO will set you back around $4m in the first two years. Most of this funding will have come from providers themselves, though CMS also made some modest central funding available.

Context does matter here. The average US per capita Medicare spend is just over $10k compared to just over £2k in the NHS. There are multiple reasons for this significant difference. It is often assumed the cost differential is due to over-use of the healthcare system. However, evidence suggests that the main drivers are higher prices both charged by healthcare providers and pharma. Part of this implies higher profits and therefore opportunities for transformative investments.

Compare that with an NHS that is severely underfunded and stretched in all directions. More often than not, we expect busy managers or clinicians to deliver change on top of day jobs. Accountable care at its purest is a radical departure for most healthcare systems. How many industries have achieved such transformation without significant investment and de-investment? Unlike the US, this money is not going to come from provider war chests.

“There is a courtesy of the heart; it is allied to love” (Goethe)

Data is important and so are incentives. Money can be found if we really meant transformation in the NHS. They set the context. But it is also the easy part. Changing behaviour of management, clinicians and patients is where the action lies. It was therefore not surprising to hear that it was this area that had travelled the shortest distance so far. Our limited sample seems representative nationally.

It is, in part, for this reason that it is remarkable that ACOs actually saved money in the first four years as Michael McWilliams’ work demonstrates. But the gains are small, not all 400 ACOs achieved savings and those doing it for longer saw higher gains. This may be due to the particularities of the benchmarks, self-selection or the fact that it takes time to actually translate incentives and investment into change. The latter hypothesis is very much supported by the experience of Gesundes Kinzigtal, an ACO in the south of Germany that has been going for nearly 12 years.

NHS productivity growth between 1997 and 2014 has been around 2.3%. However, if the savings targets of £50bn by 2020 are to be achieved, we would need to see around 5% annual productivity growth which is unlikely to come from doing things a little bit differently.

US productivity growth has not been game changing either, despite a much higher level of spending, though transaction costs are also likely to be higher in a market-based system. ACOs can save money but a lot will be flowing back into the system via shared savings schemes. No unicorn in sight that will save the day, but no reason not to pursue them nevertheless.

Financial savings are but one aspect of coordinated or integrated care, patient experience and outcomes are equally, if not more, important. Moving away from paying for activity towards outcomes makes a lot of sense.

A unique partnership

That’s why ICHP has partnered with COBIC and OptiMedis to provide hands-on support to our partners and the wider NHS in a unique capability development programme and to provide services to support data analytics, contracting & incentives and behaviour change. We are also working closely with Duke University and Mark McClellan’s team as well as the WISH team and will be sharing the practical learning at an all day forum on 27th June jointly with the Health Foundation in London.

Dr Axel Heitmueller is Managing Director of Imperial College Health Partners. You can follow Axel on Twitter.