Are LGBT+ adults in NW London being appropriately represented in our sector’s healthcare data?

Kyle Lee Crossett, ICHP Innovation Advisor, writes on the challenge to access meaningful insight about the health inequalities for the LGBT+ community in NWL.

Population health data is an increasingly important tool we use to develop a picture of the health needs and experiences of local people. Non-identifiable (often referred to as depersonalised) health data can be used to help understand:

- where new services are most needed

- where to test new health technology or medicines

- where there are inequalities in health outcomes between groups.

One of the issues when trying to use population health data to understand health inequalities is that health inequalities drive gaps in data as well as health outcomes. Poor data recording for aspects of health inequality can be driven by a lack of attention to the issue, but is also caused by bias, discrimination, or individuals avoiding services out of fear of discrimination (causing under-recording).i

As part of our response to the national AHSN network’s spotlight on LGBT+ health inequalities, we looked to assess the capacity of local primary health care data to give us meaningful insights about LGBT+ population health in NWL. We knew that there would be significantly smaller numbers of LGBT+ people recorded in primary care health records than live in NWL, but we hadn’t expected actual recording to seem so low.

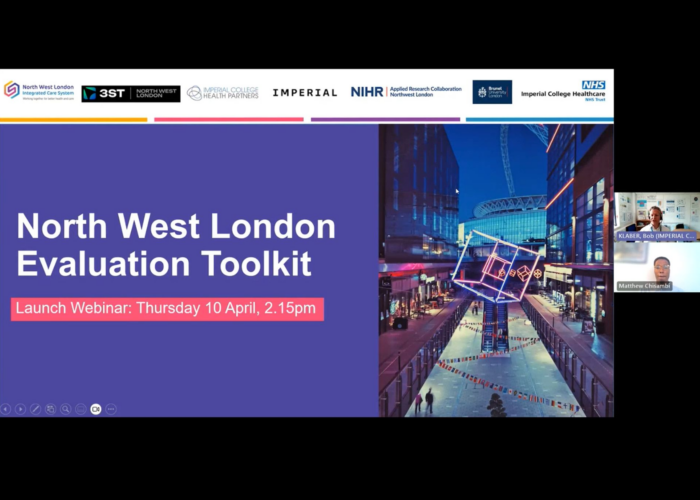

To work out the scale of under-recording, we first had to determine the approximate size of the adult LGBT+ population in NWL. It’s a little tricky to do this, as statistics on sexual orientation and gender identity tend to be collected separately, and only the former is collected in national statistics.ii However, we can get a good estimate by using the most recent population data for NWL and established figures for the percentage of LGB and transgender adults (16+) in London or the UK.iii

We looked at recording of sexual orientation and gender identity in two of NWL’s primary care data resources with these population figures in mind. The first resource, FARSITE, is a patient profiling tool used to recruit people for studies and clinical trials, covering around 190 GP practices. The second resource, Discover, is a much larger depersonalised dataset used for a wide variety of research and care planning purposes. This dataset is part of the Discover-NOW Health Data Research Hub.

Discover captured 5x more data than FARSITE, but this is still a very, very small amount of people compared to the number we would expect to see overall. Even with the most generous estimate (where we take the smallest estimates of the LGBT+ population and add together recording of LGB and transgender populations), less than 6% of LGBT+ people are recorded in primary care data.

Such low recording levels do not allow for any reliable analysis of potential health inequalities faced by the LGBT+ population in NWL. This means ICHP’s partners, who provide and commission services in NWL, are unable to access any significant data about primary care-linked health outcomes for LGBT+ people. Because of this, we are likely to miss out opportunities to improve care and to accelerate health innovations in the places they will be most useful.

The most straightforward solution to address this gap is to improve data collection. NHS England has already identified enhancing sexual orientation, inclusive gender and trans status monitoring and developing the evidence base for LGBT health inequalities as two of its four key priorities for LGBT health. In the US, there is growing evidence that better healthcare data capture of sexual orientation and gender identity can act as a health equity tool. In the UK, initiatives like NHSE and LGBT Foundation’s If We’re Not Counted, We Don’t Count have provided guidance for services to implement sexual orientation and gender identity monitoring as part of strategies to address LGBT+ health inequalities. These are critical projects but also substantive, long-term ones due to the challenges health inequalities can present to good data collection.

Because of this, it is important not to let the lack of comprehensive quantitative data lead to inaction on addressing LGBT+ population health. Specialist services in the NHS, the third sector, and most importantly, patients, are already knowledgeable about their healthcare needs and experiences.

At ICHP, our aim this year is to contribute to a conversation about how to share the information and good practice that already exists in NWL, while also asking the right questions to improve collection of population health data.

You can keep up to date about our work in this area by following us on Twitter and LinkedIn and by signing up to our quarterly newsletter.