Candice Roufosse, Clinical Reader in Renal Pathology within the Centre for Inflammatory Diseases, Department Immunology and Inflammation at Imperial College London shares her experience of engaging the public in early-stage health transformation research and shares her learning around some of the common pre-conceptions about patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE).

When I first embarked upon our early-stage PPIE for my latest research project, I couldn’t have imagined how positive a learning experience it would be. Like many researchers, the opportunities for engaging the public in my work have been few and far between.

I had undergone the appropriate training from Imperial Patient Experience and Research Centre (PERC), the Imperial Clinical Trials Unit and Imperial College Societal Engagement, and had experience of one previous engagement event and creating surveys, but never before had I had the opportunity to really explore a topic over a period of time, with a small and well-informed group of patients.

I was excited by the prospect of using engagement to support the project’s direction, rather than just check in on its success retrospectively, and, as someone with mitigated feelings towards the AI technology, was genuinely interested in whether the research was worth exploring, and in which directions.

The premise of the project was to get an understanding of how digital pathology might improve care for kidney transplant patients, but also what their expectations were for how their data might be collected, stored and used for research. Digital pathology converts biopsy features on the glass slide (“analogue”) into “digital” data. These electronic images and associated data provide opportunities for the development of tools that could make efficiencies, such as tools to make precise measurements or to mark features of interest in the tissue, or the ability to share cases easily with others for opinion. Additionally, this data can be used for research.

I partnered with Imperial College Health Partners, whose work in PPIE – specifically their data deliberations – have been quoted as best practice within Goldacre Report and Government’s Data Saves Lives strategy.

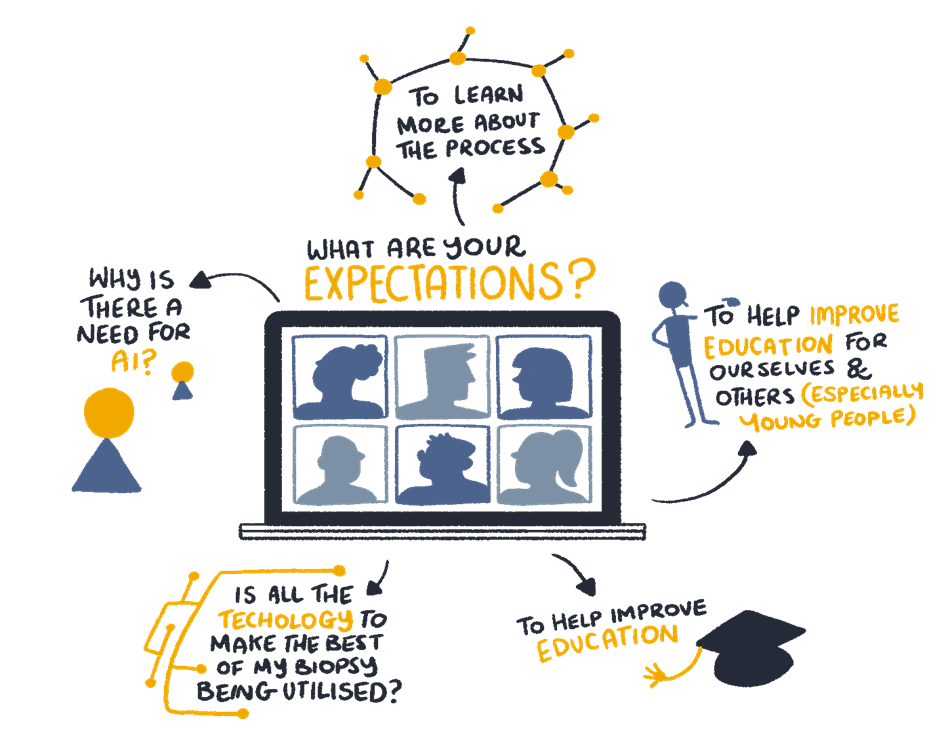

Together, we engaged a small group of 6-8 kidney transplant patients over the course of three workshops, taking the time to really inform the patient group on a topic, before opening it up to a discussion – sometimes debate! – on what really mattered to them.

I am so grateful to all the individuals who gave their time and their honest opinion, so we could begin on the journey to making their care better with them alongside us. I see those who joined the workshops is every bit a part of the project team as any of the rest of us, and I hope to obtain the appropriate investment to ensure we can get the value of their views and opinions at every stage of this project moving forward.

Here are my three biggest learnings from the experience:

Patients and the public can grasp complicated technology

Whilst the materials developed were deliberately accessible to everyone, the knowledge level on AI was far more advanced than I had anticipated. From google AI to driverless cars, our workshop group were not only able to comprehend the topic of AI but had questions about the impact that it could have on deskilling staff, or the potential for bias, which made for rich and interesting debate.

Some patients really want to get into the detail of their care

Another aspect that surprised me was how much some patients, particularly those who receive continuous or regular care like the group we engaged with, want to know about their care. The discussion around the biopsy procedure and results was impassioned and demonstrated the truly personal nature of health data and experience. Not only were we able to learn about their pain points in the biopsy process itself, we also learnt how much detail patients want shared with them, and discussed the barriers to this. As one attendee unforgettably put it – “It’s very personal because that kidney is mine!”.

PPIE requires investment, but the return is worth it.

PPIE done well costs and takes time, there is no getting around it. My experience from this event has taught me that PPIE sessions delivered purely by the research team, even if they are motivated and trained, does not compare to the results when working with a team specialised in PPIE, who bring a wealth of methods and an impartial outsider perspective. Lack of expert input risks missing the point for patients, with potential for wasted money and time in the long run and a tick box mentality around the event. The outcomes from the session on data storage and access mean that we can build the desired policy and governance into the project. The value is in the time taken and the expertise sourced. Without either, PPIE is at risk of being a token exercise that not only doesn’t have any bearing on how to deliver the project well for those it is intended to help.

Read the full PPIE case study here, or email chanelle.corena@imperialcollegehealthpartners.com for more information.